Anniversary of New Orleans Riot

Posted in Our Blog on July 30, 2014

July 30 marks the 148th anniversary of the New Orleans Riot, a critically important event in the history of American race relations, but one which isn’t well-known to many people today, even in Louisiana. It’s crucial that we understand this event that ultimately resulted in 38 people dead, and the role it played in the larger story of the period immediately following the American Civil War.

As the Civil War was coming to a close in 1865, the victorious Union government was debating how best to deal with the defeated states of the former Confederacy. Should the states be restored to fully equivalent status? Should their governments be dissolved and rebuilt, and should the government officials who had played a part in seceding from the country be punished or allowed to continue serving in government? If the elected officials who had voted to secede in the first place were allowed to lead their states again, what would prevent them from attempting to rebel in the future? These questions were made more complicated with the passage of the 13th amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery and would force the southern states to deal with their former slaves as free people. What rights would be given to former slaves, and how difficult would life be for them, and would the southern state governments honor and protect those rights?

As the aftermath of the war showed, the former Confederate states did not react well to the presence of millions of newly-freed black men and women, with violence erupting throughout the South. The question for the national government in Washington was how best to deal with the violence while rebuilding the political infrastructure. President Lincoln had favored swift restoration and readmission for the Confederacy, and he used Louisiana as an experiment for his plan after its capture in 1863. His plan was known as the Ten Percent Plan, because it required 10% of the voters in Louisiana to take an oath of loyalty to the Union; if 10% took the oath-and the state abolished slavery-the state would be readmitted to the Union and would be under control of a provisional government. Louisiana enacted this plan in 1864, but when Lincoln was murdered the next year, support for the Ten Percent Plan disappeared as members of Congress thought the plan didn’t do enough to punish the South and empower the former slaves, or else thought it went too far in violating southern rights.

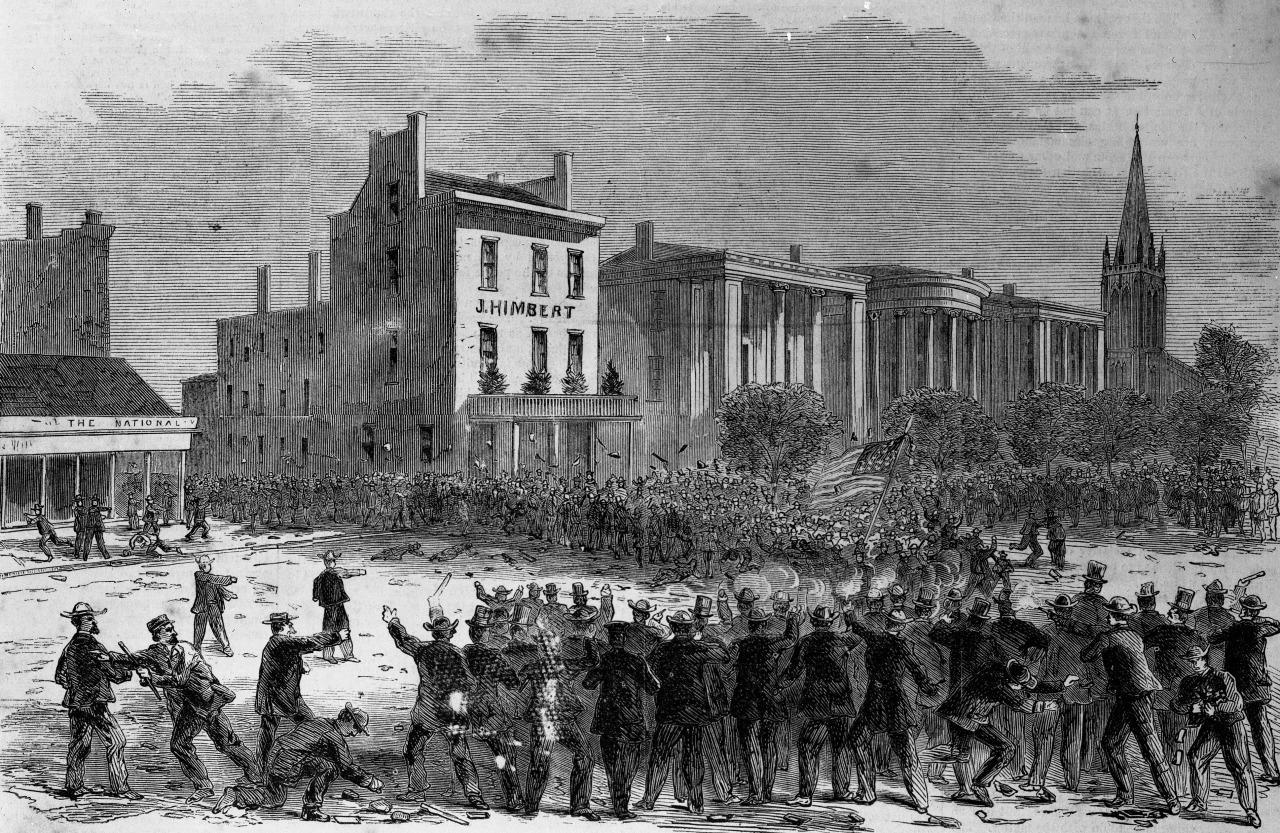

In 1866, the city of New Orleans was emerging from the martial law status under which it had been since 1863. The years of martial rule had fostered intense bitterness for New Orleanians, and when a Convention made up of mostly Radical Republicans (as progressive anti-slavery Republicans were known at the time) met at the Mechanics Institute in New Orleans to propose a new state Constitution that would give black people the right to vote, violence broke out. More than 200 black supporters, many of them Union Civil War veterans, had gathered outside the convention to show solidarity. Many Confederate veterans, flanked by New Orleans police who shared in their outrage at the idea of black suffrage, met the black demonstrators in the streets, and the violent collision resulted in 100 injuries and 38 deaths, almost all of them black.

The massacre had profound repercussions in national politics. Public backlash against the South led to the election of many more Radical Republicans, who were able to take control of Congress and enact some of the most progressive legislation of the Reconstruction era. Their goal was to not only enfranchise and empower black people, but to provide reparations for the centuries of slavery and bondage. The New Orleans Riot is a good lesson in why the goals of Reconstruction ultimately failed; it was unrealistic to expect people who were unwilling to change to accept immediate, wholesale change and to do nothing about it. The provisional Republican governments in many southern states only operated with protection from the US Army, and when the Army was removed the governments lost their ability to enforce their legitimacy. Though the law itself had changed, human nature hadn’t.

Louisiana was readmitted to the United States in 1868, and its own rule was re-established in 1877, which is the year Reconstruction is considered to have ended. The Radical Republicans in Congress had been voted out, the provisional governments lost their power in the South, and the country largely abandoned the idea of racial equality, devastating the black community and reversing the few years of progress following the Civil War.

Today, the Mechanics Institute building no longer exists; it was located where Common Street meets Rampart Street in the CBD, near the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra and the New Orleans Public Library. There are no monuments or plaques remembering the event, so it’s especially important that we not forget the New Orleans Riot and its important lessons.